My Unsavory Experience in the Food Service Industry

- Drew Scharfenberg

- Mar 4, 2023

- 20 min read

Updated: Mar 6, 2023

Consider this a "part two" of our previous episode on the topic, Episode 8: The Food Service Industry feat. Mike Campany. Except that this account will be much more unfiltered and specifically come from my perspective, as I will be moving on from my days in the service industry and I am very indignant with what I have witnessed and experienced during the past few summers. I would be doing myself and others a disservice if I did not do so.

For those of you who are unaware, I have held three different jobs during each summer following graduation from high school. During the summer of 2019, I worked for the very first time as an in-room server at the now–permanently closed Southern/French fine dining restaurant called The Side by Side, which was located in the downtown Tuscaloosa Embassy Suites hotel. The next summer, I worked at Jimmy John's 15th Street as a Sandwich Maker during the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of my friends had worked there the previous few summers, leveling up to a manager position at another location, and recommended that I apply. The last two summers, I worked at Sage Juice Bar & Speakeasy as a line cook, manning the café portion of the enterprise.

To continue residing at my home, I was required to find some sort of job for summer, so I figured that a job in the restaurant industry would be the easiest to obtain. I already liked to cook and was pretty skilled at it, certainly in comparison to my peers. I had to apply to an insane amount of jobs to even get a response, never mind an offer. This is the same critique that I will extend to my remaining service industry positions.

This unfortunate reality makes it nearly impossible for especially poorer Americans to find time to apply, especially when they are already balancing another job. Millions of Americans juggle multiple jobs to provide for themselves and their families. My view is that every job should pay a living wage. Otherwise, the business has no business existing.

Anyways, I had an interesting experience with this restaurant, earning only $2.13 an hour, which is horrifyingly legal according to the Fair Labor Standards Act (an improvement from before the act, but nevertheless another compromise between labor and capitalists) in many states for service workers, including Alabama. I will say that I earned more than the (far too low considering the rise of inflation and worker productivity) minimum wage considering tips (and this is fortunately backed legally), but nice customers shouldn't be coerced to pay the wage that the business should absolutely be paying for. I made maybe a dollar or two over the minimum wage when tips were included. But to put this figure in perspective, this would be completely inadequate to afford the yearly rent of a two-bedroom rental apartment in any American county, never mind necessities like food, healthcare, utilities, transportation, and so on. And some may contend that someone like me does not deserve a living wage merely because I was young, lived with my parents, and didn't have enough "experience". This perspective fails to consider that workers will need their savings earned from these low-paying jobs later while they are trying to find a job and stay financially afloat. But more importantly, every worker is entitled to the full value of their labor, no matter their age, residential status, or experience level, and explaining that requires a brief dive into some basic theory.

The equation above represents Karl Marx's concept of the Circuit of Capital as described in Das Kapital. M represents capital and C represents commodities (i.e. raw materials), which are acted upon by MP, means of production, and LP , labor power. These commodities turn into P, the unfinished product, and later C', the finished product that goes to market. This process generates M', the profit, for the one who owns the means of production and supplied the capital. Under capitalism, these two elements accompany one another, yielded typically by one person (or perhaps a few people), the capitalist. Under the capitalist system, the capitalist's number one goal is always to generate profits, otherwise they will not stay in business. If they have any other objectives in their endeavors, such as providing a quality product or service, donating a portion of sales to charity, or anything else, these come secondary to the profit motive. In my first job, the owner of The Side by Side, for example, used the power of their capital to fully acquire the means of production–the land, building, labor, and equipment. Capitalist societies must provide and protect "private property" (a different term from personal property, which refers to things like one's clothes, house, and so on) laws in order to allow this step. Us workers do not offer value in terms of capital or anything else, so the only thing we have to sell was our labor, via a wage. This is the case for roughly 99% of Americans, who can be designated as the true working class, or the proletariat. The remaining roughly 1% are called the capitalist class, bourgeoisie, or ruling class. It is worth noting that there is no such thing as a "lower" or "middle" class; these are mythical concepts intended to artificially divide the working class, while advancing the mutual interests of capitalists. With effectively no labor contributed from the capitalist, who instead benefitted from passive income as a result of owning the means of production, us workers created all the value for the restaurant. Whether we served customers, cooked food, or cleaned the space, our labor created economic value in the form of profits and kept the restaurant running. But in order to maximize profits, capitalists have to do at least one, if not all, of several things. They could decrease the cost of commodities as much as possible, for example purchasing the cheapest inputs (i.e. vegetables or meat) possible. Another possibility is to reduce the compensation of workers (including the wage itself or benefits such as healthcare, retirement, childcare, life insurance, paid holidays and childcare, and so on), or better yet, to thin the workforce as much as possible. These tactics are incredibly common in the service industry. Restaurants like The Side by Side or Sage weren't existing in a vacuum, they were also competing against others in the industry nearby. Competing in this sense means being as profitable as possible. And where do these profits go? Some may go back into the restaurant, perhaps to purchase new equipment or more food ingredients. In some cases for especially successful restaurants, profits may even be used for expansion of the enterprise to new locations. However, most profits go right in the pocket of the capitalist, and they may do with this newly generated capital as they wish. To provide for their basic needs and sometimes wants, the workers purchase the very products their (or other workers') labor produced, culminating in an endless cycle of more and more profit generated at the expense of the working class.

Perhaps more important is the concept of the labor theory of value, another concept developed by Marx. I will provide a rather simple explanation of this theory. Remember that workers perform all the labor that generates finished goods and thus profits? Workers are not fully rewarded by the capitalist for their work. Otherwise, capitalists would never be able to generate profits and thus their operations would fail under capitalism. Instead, workers are given back a small percentage of the value they created in the form of a wage. An even smaller percentage is taken out via taxes, the exact amount depending on the local, state, and federal tax policy. In theory, taxes should provide for the common well-being of the people–healthcare, infrastructure, and so on–but in today's United States, most of our tax money is wasted on ludicrous military spending during a time of relative peace, more funding for overfunded and militarized police, and tax breaks and other state bailouts for the ultra-wealthy and corporations. However, the largest chunk of the value created by the worker is transferred directly to the capitalist. This is the profit. One can quickly see how this system is inherently exploitative of the worker. This Ted Talk explains the process in more detail, as well as this video featuring economist Richard Wolff. Regardless of whether the capitalist is "nice", the compensation is better relative to another enterprise, or any other excuse, the worker clearly is worse off in this exchange. And the power structures and strict hierarchy between capitalist and worker remain the same no matter where one is employed. Despite the rhetoric that is all too historically commonplace in both corporate and reactionary America that workers are lazy and just want to "get free stuff", it is the capitalist who is clearly lacking in meaningful contributions. In fact, the entire operation of the capitalist rests upon the capitalist failing to adequately compensate the worker for their work, instead taking the value generated by the worker for themselves. There is an endless unsolved struggle between the worker, who wants to be paid as much as possible to adequately provide for their material needs, and the capitalist, who wants to compensate them as little as possible to maximize profits. This struggle is where I found myself as I entered the workforce for the very first time.

After searching countlessly online for other summer job opportunities or even applying in person, I found myself coerced into selling my labor for a wage, even though I had no knowledge of this process at the time. $2.13 (or $7.25) an hour is better than $0 an hour sitting at home, right? There is something deeply troubling about a system that only allows for those two atrocious options for anyone, especially considering that a living wage for a single person in Tuscaloosa County is at least $16.47. However, this figure assumes that the employee works full-time, which was certainly not the case with my seasonal, part-time employment with Side by Side. My point here is that I would have been toast if I had been out in "the real world" on my own trying to survive, especially if I had worked in an area with higher costs of living. A point commonly raised by capitalist apologists asserts that these alarmingly low-paying service jobs are worked by high school or college students, not full-time adults. At my first job, and every one after that, this was anything but the case. I could name a number of coworkers at The Side by Side who were well past these ages, yet still working this job alongside me, a fresh graduate from high school and naive teenager. And to further refute this notion, at least with regard to high schoolers, what about all the service industry jobs around the nation that operate during the school year from 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.?

One of the things I enjoyed at The Side by Side was the positive interaction I had with my coworkers, which would become a theme at following jobs. I enjoyed conversations with a fellow worker by the host stand, sharing our future aspirations or otherwise relishing each other's company. On Saturday nights, we might be joined by the Pittsburgh-based piano man, who played beautiful tunes and was a pleasure to talk to. My older server co-workers were quick to take me under their wings and help me complete my duties as an in-room server. In the kitchen, the staff were friendly. I loved talking to one of the chefs and learning about what he was cooking next. Even though he was significantly older than me, we had a lot in common, and once he offered me a slice of a watermelon sporting an unusual yellow flesh after I pointed it out. That is still the best-tasting watermelon I eaten to this day. I remember he told me once that he commuted from Hoover, AL, at least an hour each way, to work at the restaurant. I could only imagine the inconvenience of time as a consequence, but now I can imagine much more–the cost of gas and maintenance of his beat-up sedan, the lack of benefits at our restaurant, and the absence of other job opportunities closer to his residence. I had some really neat gastronomic experiences while working there, for example, a mousse made out of a fruit that I never thought could taste so good. But it was horrifying to ponder the major dent of my measly check ordering one of these tasty food items would take after the few poorly compensated hours of my shift. I felt very torn and guilty the handful of times I made this choice.

I had some interesting experiences during that summer. One time, after I brought my food cart into the adjoining hotel and into a room, I dropped a glass in front of a guest, which littered the floor. I was incredibly defeated as I retrieved a broom downstairs and returned to sheepishly clean the mess. Another time, I heard otherworldly, terrifying noises coming from a room I was delivering to and recruited a security guard to accompany me. They keyed into the space, only to find the guest fast asleep on the couch and the TV still on as I left the platter of food on the counter. One night someone called the restaurant phone, asking if we served dog. I figured it was a joke, but I pretended to take the inquiry seriously. "Dog? No sir, we don't serve dog here." A few seconds later I received the man's slurred threat: "Well if y'all don't serve dog, I'ma come and shoot you up!" It was an older phone, so once I hung up, the phone number information of the caller was unfortunately lost. Otherwise, he might have met consequences for his actions. I notified management about the threat and they notified security and the police; long story short, we closed the restaurant early and were escorted to our vehicles by police. That night was certainly an eye-opening experience in terms of the sometimes difficult customers that would have to be dealt with in the service industry. During all this activity and creation of value, upper management was effectively nonexistent, nowhere to be found. And despite meeting some wonderful people along the way, I would not miss this job after leaving for college at the end of the summer.

The next summer, after another unnecessarily intensive job search, I landed a job at Jimmy John's 15th Street after a recommendation from a friend, who was a manager at another location in town. The pay was a a slight improvement from my first job, but not not by much, coming in at $9.50 an hour. The work was extremely repetitive and mind-numbing, whether I was retrieving ingredients from the freezer, cleaning the bathroom, preparing the bread, slicing veggies or meat, taking orders, or making sandwiches, as my title suggested. Also, the benefits were nonexistent; the closest thing to a benefit was a measly 15% off a sandwich. My coworkers were not as noticeable as the previous summer. I got along with everyone, but I did not make any lasting friends. One day after I clocked out and was walking to my car, one of my coworkers stopped me and encouraged me to invest in Crypto to make more money on the side. I didn't know anything about it at the time, so I obliged and we exchanged contact information.

Thankfully, I never pursued that avenue, because we now know how dangerous an investment Crypto is, not to mention the wealth inequality that cryptocurrency perpetuates, which is somehow even greater than Wall Street's. El Salvador lost $60 million dollars in just one year after making a reckless bet on Bitcoin. Many of my coworkers, including the Crypto guy, had already been indoctrinated by the "grindset" culture, which has captured millions of Americans. Think of the lifestyle "coaches", the multi level marketing schemes, and the Andrew Tate's of the world. These people falsely believe (and try to indoctrinate others to believe) that they can become rich just by "hustling"–taking on multiple side jobs (such as being an Uber driver), investing in very volatile investments such as crypto, putting is unhealthy working hours, and so on. This perpetuates the already prevalent culture of overwork (conversely with a stark lack of benefits compared to other Global North nations) in America and promotes a toxic petite bourgeoisie attitude among members of the "grindset" community, in which they mistakenly believe that they can rise above the working class by "picking yourself up by your bootstraps". Ironically, this phrase was originally intended to highlight the absurdity of trying to do something physically impossible. This dissolution of labor into "hustling" hinders class consciousness and worker solidarity. As workers, we should all be uniting together to strive for better compensation, working conditions, and democracy in the workplace, instead of selfishly pursuing a pipe dream that a very privileged few will even have a chance of achieving.

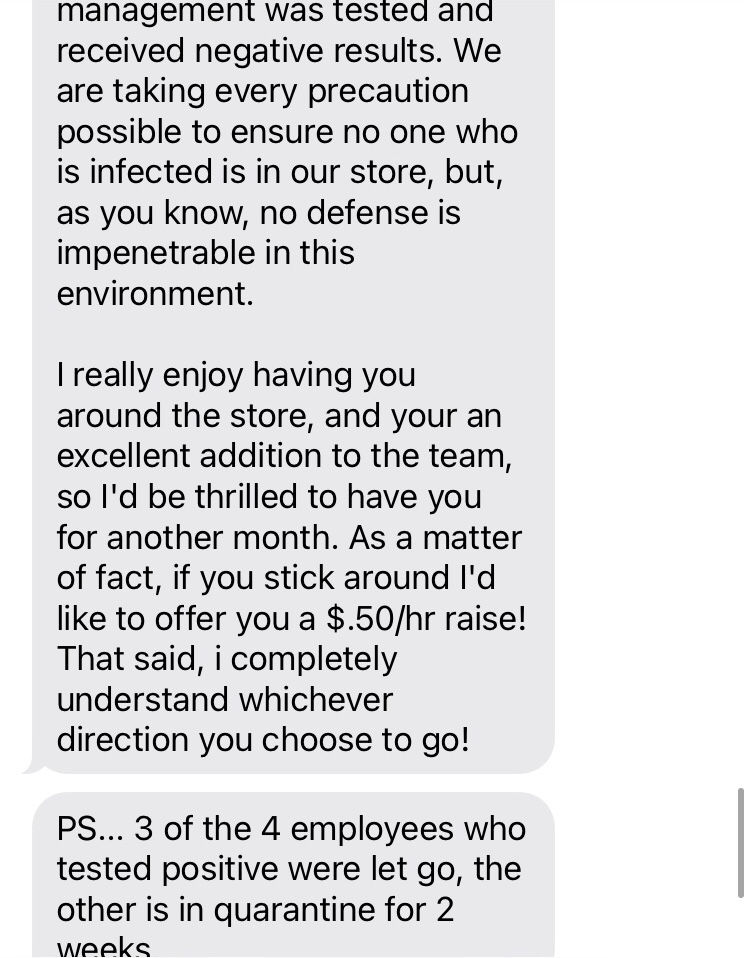

Anyways, I did not enjoy this job. I was underpaid, occasionally had my sensitive ears blown out by the drive-through headset, and I was not even cooking. Instead, as detailed earlier, I performed very menial, repetitive tasks. This was also during the middle of the pandemic and us "essential" workers put ourselves and our families on the line every day to keep the business running for capitalist profits, who were able to hunker down at home without risk of catching COVID-19. In yet another display of the process of exploitation, the capitalist class would grow in wealth during the pandemic, while the working class were left even more exposed than before. Of course, there was no health insurance, paid leave, or anything else to help if we came down with the virus at Jimmy John's. One day, we had a rush of drive-through customers and the manager handed me a precooked turkey, wrapped in several layers of plastic, and asked me to cut the plastic off over the sink. He handed me a large serrated breadknife (the worst possible tool for the job) and I began the task without thought of questioning. But my hand slipped as the turkey juices oozed out, and I accidentally cut my left index finger. Blood immediately erupted from the laceration as I ushered myself to the opposite sink, away from the potential view of customers. The blood would not stop running and I asked the manager if I could have a bandage and other medical supplies to properly clean my finger and stop the bleeding. But he could not find anything and I had to wait for 10 or 15 minutes with my finger hovered over the sink, as my the manager drove in his minivan to a nearby pharmacy. I was patient, but understandably irritated that there was no medical equipment in the shop. The cut was fairly severe and would require surgical glue to keep intact. Thankfully, the injury was fully covered by worker's comp. I did not go back to work for a week or so, and the scar is still visible to this day. Another issue came to the forefront later in the summer, as news of "COVID parties" in the college town spread, in which people partied together in large groups to purposely catch the virus. I became aware that several other coworkers were involved in this trend and I was immediately alarmed about potentially being exposed at work, so I brought it up to the manager in the following text exchange.

It was such a laughable offer, a slap in the face really, now that I look back back on it. $0.50 an hour is hardly an improvement, and certainly would not outweigh the medical costs if I stuck around and caught the virus. Needless to say, I would happily end my Jimmy John's position earlier than I planned to, never to return.

Finally, my last two summers were spent at Sage Juice Bar & Speakeasy in downtown Tuscaloosa, located in a former train depot known as Temerson Square. For a long time, I was very impressed with my position at Sage. It still wasn't a high-paying job by any means, but I enjoyed the work and made lots of wonderful friends, many of whom I still keep in touch with. During my only interview with Ken in May of 2021, he seemed very impressed with me and even said, effectively, that "I've already looked at your resume and think you would do well here. It's just a matter of whether you want to join us." No potential employer had ever told me anything like that before, so in that moment I felt valued and special. Ken also offered more money ($12/hour the first summer and increased by $2/hour the next after brief negotiation for the second summer) than the competing job opportunity at the time with Panera Bread ($11/hour, I think), so the decision was a no-brainer. The wages were nicer compared to my previous jobs. Of course, this is the service industry, so necessities like healthcare coverage, paid medical leave, and so on were not on the table. But I really appreciated the invitation to make my own free meal for lunch everyday. My coworkers would frequently share the smoothies or acái bowls they had prepared with me as well. Compared to my previous positions, this one admittedly fed me much better. My coworkers were really amazing people, overall the best I had ever encountered. During both summers with Sage, I truly enjoyed my time speaking with coworkers, whether we were cracking jokes, sharing new music with each other, venting about management or personal issues, or having deep conversations about a variety of topics. During those two summers, I was introduced to lots of new musical artists who would later populate my playlists, including Glass Animals and Oliver Tree.

But Sage was plagued by a host of problems, the least of which was the rodent issue (pest control showed up quite often to set traps and on more than one occasion I had to dispose of dead mice). The first warning sign rose to the surface shortly after I had joined Sage, when one family member pointed out that the lack of a method of direct deposit was very strange. I had turned in all the necessary forms (including the W-2) and information to my employer, but we were paid only with pay stubs. I was naive, as I still did not totally understand the expectations in this area of the service industry. At the end of the summer, I left for my junior year of college early, as I was required to arrive at the end of July for RA training. I had notified Ken well in advance, at least two weeks before as is standard, that I would be leaving at that time. He understood. Our checks were distributed every other Friday, and I left several days before then, so we agreed that Ken would mail my last check to campus. I provided my address shortly after I returned to college, as detailed below in our text exchange:

He ghosted me for months after that last message, refusing to answer my texts or multiple calls. I even called the main Sage line to get someone to have Ken explain the whereabouts of my check, but even that did not work. After talking with my family about the situation, one of them agreed to drive to Sage to physically obtain my last check. According to them, they walked into the establishment, but Ken was not there, so they approached Cheyenne, Ken's wife and the other manager. During the course of their exchange, Cheyenne behaved "oddly and awkwardly", as they later explained to me. She eventually agreed to fetch my check in the back office, but oddly, it took roughly ten or twelve minutes minutes to complete the task. We highly suspect that the check was never written to begin with, given Cheyenne's behavior, Ken's no-response, and the time it took to "fetch" the check. Instead, Cheyenne had likely written my last check on the spot in the office, as Ken seemed to have never intended to pay me, and thus had lied about sending my check in the first place. He might have assumed that a naive college student like me would forget about it, and even if I remembered, I would be too busy with my various college duties to bother.

Yet, despite the warning signs, I returned the next summer. I enjoyed my coworkers, free lunch, and job security (I would not have to yet again pump out an absurd amount of job applications just to find another dead-end service job) enough that I decided to return. Most of the summer was uneventful. We were still paid in stubs, but I still enjoyed the time with my coworkers and such. But towards the end of the summer, I quickly became aware of some incredibly damning allegations concerning management at Sage. For starters, the bartenders accused Ken and management of stealing their tips. They received several very large tips that summer, and noticed that their paychecks reflected only a small fraction of those figures. Several employees were reportedly victims were of wage theft, in which the compensation they received did not reflect what they should have received, as calculated by multiplying the number of hours worked by the agreed-upon wage per hour. To this day, many former employees of Sage reported that they still have not been compensated, which constitutes wage theft. Employers steal over $15 billion in wages from workers every year, which violates the very (purposely inadequate) laws that the ruling class helped create, and Sage reportedly added to this theft. It was also apparent that taxes were not being withheld from our paychecks, which made our tax returns much more difficult, but this was the least of our worries. We were effectively paid "under the table" with no knowledge of our existence as workers to the proper authorities, such as the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) or Department of Labor (DOL). This also implied that Sage was not paying the mandated unemployment tax nor workers compensation, which had severe consequences for workers. "In addition to putting us in jeopardy with the IRS, the practice of paying us under the table with checks instead of official pay stubs makes it near impossible to receive unemployment benefits or be able apply for necessities such as apartments or cars, as we are unable to provide agencies with official pay stubs to prove employment. One employee had this issue recently when they were required to submit three pay stubs to qualify for an apartment, but they could not use any materials from Sage as they did not qualify as legitimate income." Numerous other issues prevailed, including the failure to provide adequate protection to bartenders who were subjected to sexual harassment and potential attempted sexual assault by themselves late at night, a drawn-out, passive-aggressive process of terminating employees that would leave them progressively more socioeconomically vulnerable, and woefully inadequate training practices. The Sage Juice Bar Workers' Letter explains the plight of workers in greater detail.

Just before I left for my senior year of college, the letter was placed under some papers on the counter. When management found it, they made a few marginal improvements, but in the areas of the least concern. They certainly did not address issues such as allegations of wage theft. A few months after I left, Sage would permanently close down, in an epic display of karma. The Sage Instagram account posted a video in late November 2022 apologizing for shutting down and explaining the conditions which led to their demise. Of course, no mention was made of the horrific treatment of workers or the futility of management. They scapegoated their financial struggles on their bad luck, claiming that they barely missed out on the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans designed to help small businesses impacted by the onset of the pandemic. Assuming this claim is true, it would still give them no right to abuse workers as they alleged. Rightly so, their comment section featured many employees, but mostly patrons, who were enraged at the wage theft and other exploitation of workers that frequently occurred, according to them. The comments were so hostile in fact, that Cheyenne quickly turned the comments off, and they are now no longer visible to the public. In the following weeks, after several calls with former employees, I discovered that Ken was also in deep trouble with the landlord for not paying rent for months. I was even told by one of my coworkers, who along with another coworker had been designated as having partial ownership in Sage, that Ken had omitted them from the legal documentation and thus they had received nothing that they were promised.

To reiterate, Ken (and Cheyenne) reportedly stole wages, actively prevented necessary safety measures for my fellow coworkers, and committed numerous other offenses that hurt the workers at Sage. To my knowledge, Sage management has still not compensated a number of employees for their dedicated labor, whether it be stolen wages, stolen bar tips, or anything else. Given the countless offenses they likely committed during their stint as managers and owners of Sage, they should never again occupy a position of any authority in the workplace, which certainly includes the position of an owner or manager (a.k.a. a capitalist). Even by the standards of capitalism, Ken was deemed by many a sorry excuse for a manager and owner and should have never been allowed the responsibility to run his own business. In fact, no one should ever be able to become a capitalist, as it necessitates the exploitation of all workers in the relationship and is wholly devoid of democratic decision making.

And that's it for my experience in the food service industry. Inshallah, that will be the uttermost limit of my experience with the food service industry. And while this article may seem mostly negative, please do not succumb to doomerism. My experience is encouragement and further proof that workers should unite to oppose all exploitation and fight for their mutual interests, as we did to an extent while working at Sage. This action may manifest itself in a variety of ways—general strikes, mutual aid, forming unions, forming worker co-ops, agitation, education, canvassing, and so on. Form strong relationships with fellow workers and normalize discussing wages and other germane topics with them. Speak up when there is injustice committed against anyone, whether it is you or someone else. "Nobody's free until everyone's free", as the Civil Rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer once exclaimed. Especially with my experience at Sage, I have learned that we desperately need widespread democratic control of the workplace. In the United States, we love to think of ourselves as a "liberal democracy" (which is incredibly problematic, but a topic for another time), yet our workplaces represent a dictatorship of capital. The capitalist (and perhaps upper management as well) and their capital have the final say on nearly all decision-making processes within the firm to the detriment of those lower in the hierarchy, even though the workers generate effectively all the labor that yields profit. Under today's neoliberal hegemony, workers hardly have any choice but to stay silent about their concerns and accept their higher-ups' demands, or else face being fired or otherwise negatively impacted. The same deeply hierarchical and oppressive relationship exists with nearly every workplace, outside of a select few worker co-ops, so this exploitative relationship cannot simply be avoided by changing workplaces. Having a democratic participation model within Sage could have even prevented the fall of the enterprise, because management tasks could have been better distributed among everyone involved and workers would have been able to provide crucial input and suggestions given their experience on the front line of labor. By rising up and employing proven methods mentioned above, we can win much deserved compensation, benefits, representation, and a healthier, more free life for all. Imagine if American workers reacted to injustice committed by employers (or the state) as the French did recently, when a bill proposed to raise the retirement age by two years. We have the power, as workers, to bring the profits of a single business, or even the economy, to a standstill until our demands are met if we organize. There are, after all, a lot more of us than them.

Comments